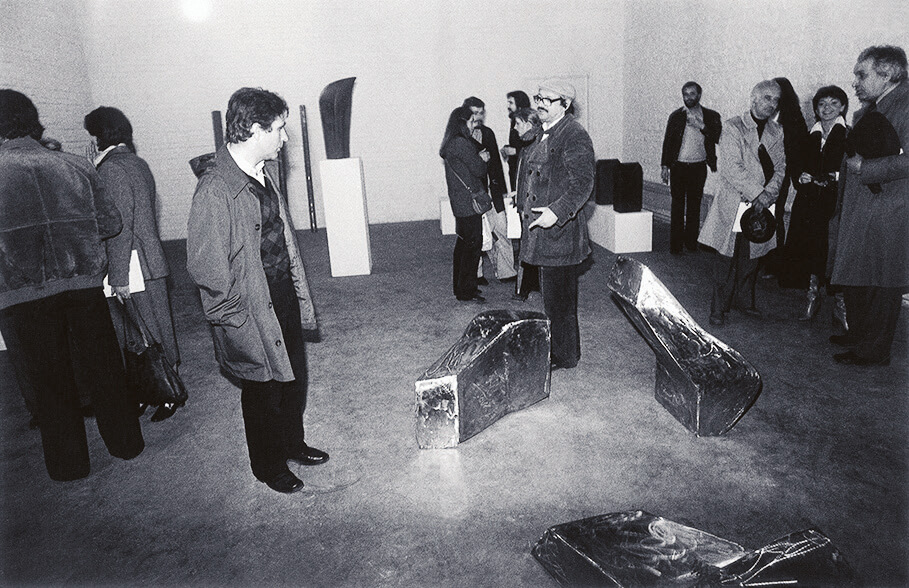

The foreword from the exhibition catalogue Gallery SC, 1980

Tonko Maroević

The first solo exhibition is always not only a particular test for a young artist but also an unusual challenge to the public. With this act, the creator lays accounts before himself and before others and looks at his work in continuity: if until then he was allowed to try his hand at different fields, look at others and look up to others, the occasion of a collective showing of a large number of works necessarily raises the question of common denominator, coverage, and identity. But as it is necessary for the author to discover and confirm his career as an independent being, so the audience and critics should take on the obligation to respond to that work, overcome specific features (if any), and fit his eventual novelty into the existing system (with appropriate change of the whole – as T. S. Eliot warned).

For a young sculptor, the first exhibition is a particular problem. In addition to the ritual initiation, the purification from the sediments of school plantings (from the “original sin” of the Academy – as I asserted a long time ago with some exaggeration), he must also show appropriate resourcefulness within the bounds of the inevitably limited means of expression. While there are more or less available to the novice painter the same technical possibilities as his predecessors, and he can win his version in free competition”, at the start, the sculptor usually has to be satisfied with a bad choice of materials (various substitutes, insufficient quantities, and reduced dimensions) for his spatial and design visions. Therefore, realizations and manifestations of the new spirit in sculpture are rarer than in painting. Sculptor Peruško Bogdanić presents himself with the first exhibition, fully aware of the aforementioned situation. However, he knew how to emerge from difficulties, limitations, and some advantages to make his expression suitable for a new beginning. His beginning, by a happy confluence of circumstances, coincided with the beginning of the species, with questioning only the sculpture’s appearance and the search for its essential elements. Clearing away immediately with the academic epidermomonus, he headed for a smooth surface and a precise measure, for volume and core, for primary forms and figures. In the works shown so far, Bogdanić has touched several edges and examined the properties of different instruments and substances, but always in the sign of ultimate reduction. At first, he made minimalist constructions in painted wood, following minor deviations from the default and usual geometric order. Then he closed the spatial grids with metal sheets and wires, activating the interior and exterior of the sculpture with small movements. Finally, he turned to elemental signs, solid, stable prisms, and obelisks, with a distinct symbolic tension. Even in everyday moments, Bogdanić is familiar with various materials and different processing methods. But it is no longer about improvised means but precisely about the deliberate search for a good echo and the “right tone”. After sketching clay and plaster, he checks the forms in bronze-patinated, silver-plated, and electroplated forms. It is not by chance that he chooses a classic sculptural technique in which austerity and the brevity of his motifs and signs come to a unique expression; that is, he wants to distinguish himself from traditional sculptures by attitude, not just execution. The closed cycle of Bogdanić’s works represents variations on the theme. Associatively touching everyday forms (such as a tower or a column, a wedge or a finger), its forms do not strive for recognizability, that is, metaphorical connotations, but strive for the effect of some rudimentary, irreplaceable and irreplaceable figure. It is about a kind of primary structure in which each member is independent, complete, and simultaneously usable in complex combinatorics of elements. So, every statue by Bogdanić is first a moneme and a morpheme, and then a syllable or joint of a complete sculptural system. Suppose we use the already mentioned idea of a new beginning. In that case, we will say that he spells the alphabet of primary spatial forms, returning after schooling to the very origin (craft and meaning).

Starting from the pyramid, the cylinder, and the cone, the author placed his own heterodox, non-geometrical bodies in the space. He emphasized the tension of the surfaces and the tactility of the edges with a summary – but therefore no less obvious – modeling; he adopted them with an organic trace and a human scale. It is interesting that despite the fundamental equality of the sights (the processing mainly allows us to place them both upside down and lying down, to look at them both up and down), Bogdanić’s statues naturally aim for the vertical. This, however, is not a human-like vertical nor a dendromorphic buoyancy, but rather a provoking of gravity and the capturing of elongated shadows on the smoothed sides. Pivoted in space like cones or houses, they enable games of stacking and breaking down, addition and multiplication. In a word: variation with a given constant. The exhibition should check how the walls and floors will accept them and how they will resonate in the environment. Still, we can already conclude that they were made strictly and consistently, that they were executed lege artis and that they testify to a specific intellectual profile and intuitive openness of their author.